In the previous article in this series, we had an extensive discussion on the Go

net/http package and how it can be used for production-ready web applications.

We focused mostly on the routing aspect and other quirks and features of the

http.ServeMux type.

This article will close out the discussion on ServeMux by demonstrating how

middleware functions can be implemented with the default router and introducing

other standard library packages that are sure to come in handy when developing

web services with Go.

Middleware in Go

The practice of setting up shared functionality that needs to run for many or all HTTP requests is called middleware. Some operations, such as authentication, logging, and cookie validation, are often implemented as middleware functions, which act on a request independently before or after the regular route handlers.

To implement middleware in Go, you need to make sure you have a type that

satisfies the http.Handler interface.

Ordinarily, this means that you need to attach a method with the signature

ServeHTTP(http.ResponseWriter, *http.Request) to the type. When using this

method, any type will satisfy the http.Handler interface.

Here's a simple example:

package main

import "net/http"

type helloHandler struct {

name string

}

func (h helloHandler) ServeHTTP(w http.ResponseWriter, r *http.Request) {

w.Write([]byte("Hello " + h.name))

}

func main() {

mux := http.NewServeMux()

helloJohn := helloHandler{name: "John"}

mux.Handle("/john", helloJohn)

http.ListenAndServe(":8080", mux)

}

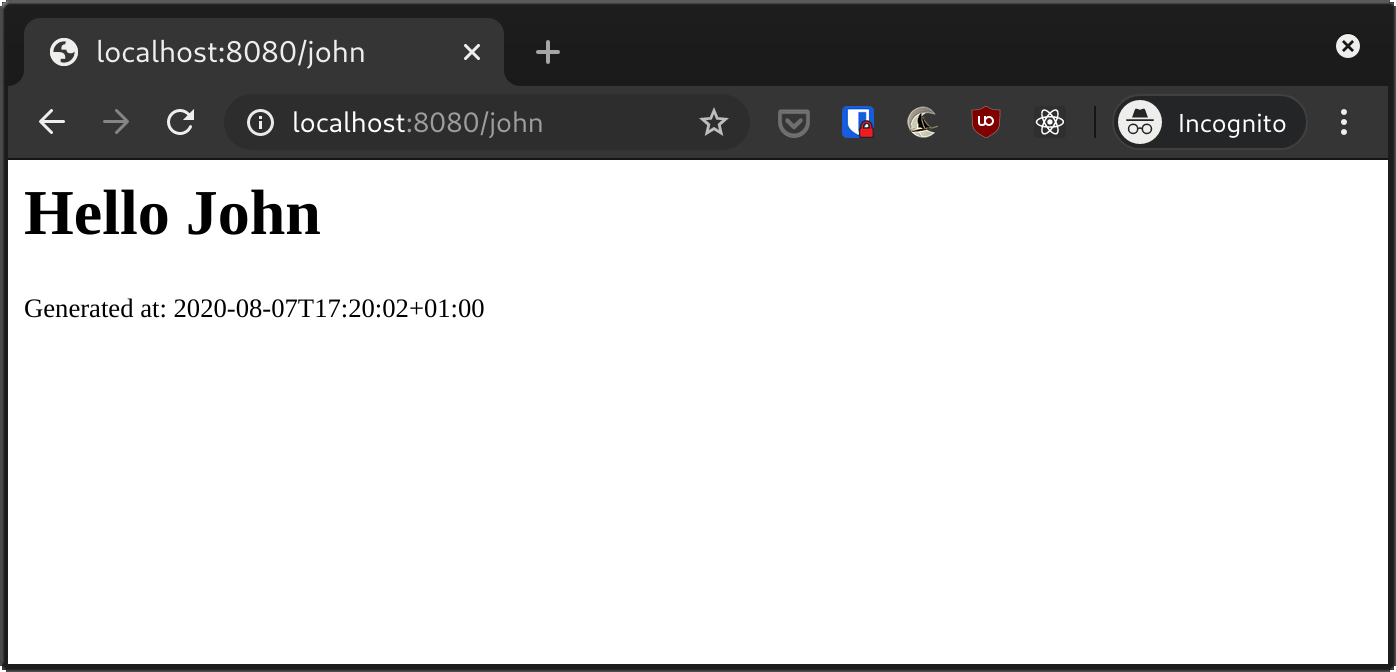

Any request sent to the /john route will be passed straight to the

helloHandler.ServeHTTP method. You can observe this in action by starting the

server and heading to http://localhost:8080/john.

Having to add the ServeHTTP method to a custom type every time you want to

implement an http.Handler would be quite tedious, so the net/http package

provides the http.HandlerFunc type, which allows the use of ordinary functions

as HTTP handlers.

All you need to do is ensure that your function has the following signature:

func(http.ResponseWriter, *http.Request); then, convert it to the

http.HandlerFunc type.

package main

import "net/http"

func helloJohnHandler(w http.ResponseWriter, r *http.Request) {

w.Write([]byte("Hello John"))

}

func main() {

mux := http.NewServeMux()

mux.Handle("/john", http.HandlerFunc(helloJohnHandler))

http.ListenAndServe(":8080", mux)

}

You can even replace the mux.Handle line in the main function above with

mux.HandleFunc and pass the function to it directly. We used this pattern

exclusively in the previous article.

func main() {

mux := http.NewServeMux()

mux.HandleFunc("/john", helloJohnHandler)

http.ListenAndServe(":8080", mux)

}

At this point, the name is hardcoded into the string, unlike before when we were

able to set the name in the main function before calling the handler. To

remove this limitation, we can put our handler logic into a closure, as shown

below:

package main

import "net/http"

func helloHandler(name string) http.Handler {

return http.HandlerFunc(func(w http.ResponseWriter, r *http.Request) {

w.Write([]byte("Hello " + name))

})

}

func main() {

mux := http.NewServeMux()

mux.Handle("/john", helloHandler("John"))

http.ListenAndServe(":8080", mux)

}

The helloHandler function itself does not satisfy the http.Handler

interface, but it creates and returns an anonymous function that does. This

function closes over the name parameter, which means it can access it

whenever it is called. At this point, the helloHandler function can be reused

for as many different names as necessary.

So, what does all this have to do with middleware? Well, creating a middleware function is done in the same way as we've seen above. Instead of passing a string to the closure (as in the example), we could pass the next handler in the chain as an argument.

Here's the complete pattern:

func middleware(next http.Handler) http.Handler {

return http.HandlerFunc(func(w http.ResponseWriter, r *http.Request) {

// Middleware logic goes here...

next.ServeHTTP(w, r)

})

}

The middleware function above accepts a handler and returns a handler.

Notice how we're able to make the anonymous function satisfy the http.Handler

interface by casting it to an http.HandlerFunc type. At the end of the

anonymous function, control is transferred to the next handler by invoking the

ServeHTTP() method. If you need to pass values between handlers, such as the

ID of an authenticated user, you can use the http.Request.Context() method

introduced in Go 1.7.

Let's write a middleware function that simply demonstrates this pattern. This

function adds a property called requestTime to the request object, which is

subsequently utilized by helloHandler to display the timestamp of a request.

package main

import (

"context"

"net/http"

"time"

)

func requestTime(next http.Handler) http.Handler {

return http.HandlerFunc(func(w http.ResponseWriter, r *http.Request) {

ctx := r.Context()

ctx = context.WithValue(ctx, "requestTime", time.Now().Format(time.RFC3339))

r = r.WithContext(ctx)

next.ServeHTTP(w, r)

})

}

func helloHandler(name string) http.Handler {

return http.HandlerFunc(func(w http.ResponseWriter, r *http.Request) {

responseText := "<h1>Hello " + name + "</h1>"

if requestTime := r.Context().Value("requestTime"); requestTime != nil {

if str, ok := requestTime.(string); ok {

responseText = responseText + "\n<small>Generated at: " + str + "</small>"

}

}

w.Write([]byte(responseText))

})

}

func main() {

mux := http.NewServeMux()

mux.Handle("/john", requestTime(helloHandler("John")))

http.ListenAndServe(":8080", mux)

}

Since our middleware function accepts and returns an http.Handler type, it is

possible to create an infinite chain of middleware functions nested inside each

other.

For example,

mux := http.NewServeMux()

mux.Handle("/", middleware1(middleware2(appHandler)))

You can use a library like Alice to transform the above construct to a more readable form such as:

alice.New(middleware1, middleware2).Then(appHandler)

Templating

Although the use of templates has waned with the advent of single-page applications, it remains an important aspect of a complete web development solution.

Go provides two packages for all your templating needs: text/template and

html/template. Both of them have the same interface, but the latter will

do some encoding behind the scenes to guard against code injection exploits.

Although Go templates aren't the most expressive out there, they get the job done just fine and can be used for production applications. In fact, it's what Hugo, the popular static site generator, bases its templating system on.

Let's take a quick look at how the html/template package may be used to send

HTML output as a response to a web request.

Creating a template

Create an index.html file in the same directory as your main.go file and

add the following code to the file:

<ul>

{{ range .TodoItems }}

<li>{{ . }}</li>

{{ end }}

</ul>

Next, add the following code to your main.go file:

package main

import (

"html/template"

"log"

"os"

)

func main() {

t, err := template.ParseFiles("index.html")

if err != nil {

log.Fatal(err)

}

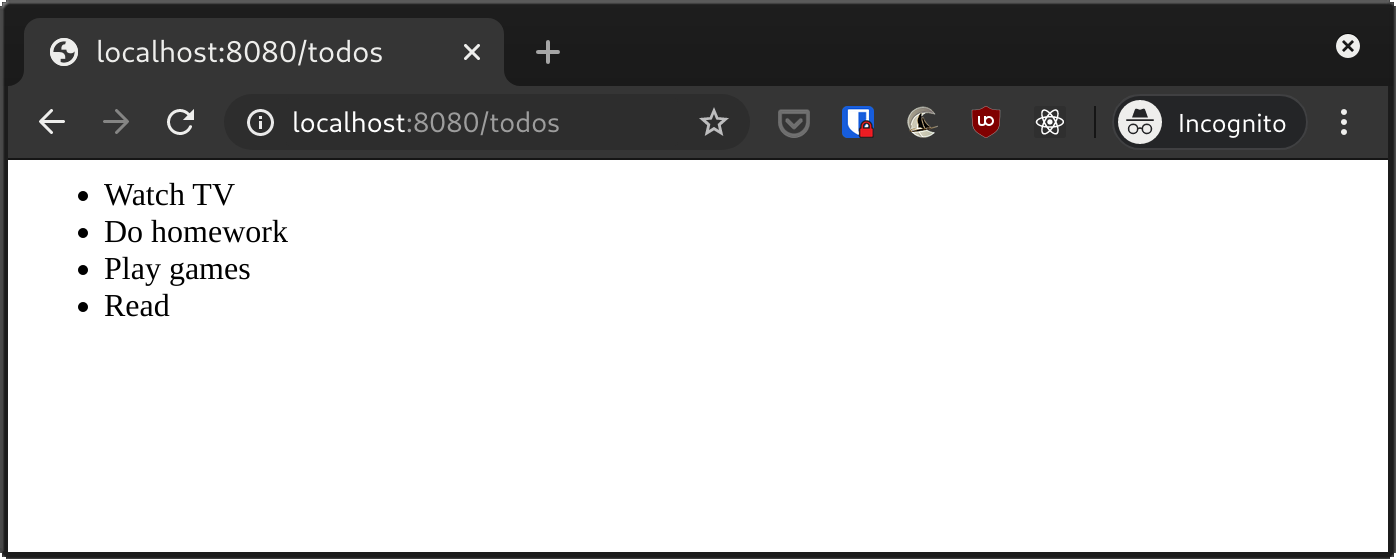

todos := []string{"Watch TV", "Do homework", "Play games", "Read"}

err = t.Execute(os.Stdout, todos)

if err != nil {

log.Fatal(err)

}

}

If you execute the above program with go run main.go. You should see the

following output:

<ul>

<li>Watch TV</li>

<li>Do homework</li>

<li>Play games</li>

<li>Read</li>

</ul>

Congratulations! You just created your first Go template. Here's a short explanation of the syntax we used in the template file:

- Go uses double braces (

{{and}}) to delimit data evaluation and control structures (known as actions) in templates. - The

rangeaction is how we're able to iterate over data structures, such as slices. .represents the current context. In therangeaction, the current context is the slice oftodos. Inside the block,{{ . }}refers to each element in the slice.

In the main.go file, the template.ParseFiles method is used to create a new

template from one or more files. This template is subsequently executed using

the template.Execute method; it takes an io.Writer and the data, which will

be applied to the template.

In the above example, the template is executed to the standard output, but we

can execute it to any destination, as long as it satisfies the io.Writer

interface. For example, if you want to return the output as part of a web

request, all you need to do is execute the template to the ResponseWriter

interface, as shown below.

package main

import (

"html/template"

"log"

"net/http"

)

func main() {

t, err := template.ParseFiles("index.html")

if err != nil {

log.Fatal(err)

}

todos := []string{"Watch TV", "Do homework", "Play games", "Read"}

http.HandleFunc("/todos", func(w http.ResponseWriter, r *http.Request) {

w.Header().Set("Content-Type", "text/html")

err = t.Execute(w, todos)

if err != nil {

http.Error(w, err.Error(), http.StatusInternalServerError)

}

})

http.ListenAndServe(":8080", nil)

}

This section is only meant to be a quick intro to Go’s template packages. Make sure to check out the documentation for the text/template and html/template if you’re interested in more complex use cases.

If you're not a fan of how Go does its templating, alternatives exist, such as the Plush library.

Working with JSON

If you need to work with JSON objects, you will be pleased to hear that Go's

standard library includes everything you need to parse and encode JSON through

the encoding/json package.

Default types

When encoding or decoding a JSON object in Go, the following types are used:

boolfor JSON booleans,float64for JSON numbers,stringfor JSON strings,nilfor JSON null,map[string]interface{}for JSON objects, and[]interface{}for JSON arrays.

Encoding

To encode a data structure as JSON, the json.Marshal function is used. Here's

an example:

package main

import (

"encoding/json"

"fmt"

)

type Person struct {

FirstName string

LastName string

Age int

email string

}

func main() {

p := Person{

FirstName: "Abraham",

LastName: "Freeman",

Age: 100,

email: "abraham.freeman@hey.com",

}

json, err := json.Marshal(p)

if err != nil {

fmt.Println(err)

return

}

fmt.Println(string(json))

}

In the above program, we have a Person struct with four different fields. In

the main function, an instance of Person is created with all the fields

initialized. The json.Marshal method is then used to convert the p structure

to JSON. This method returns a slice of bytes or an error, which we have to

handle before accessing the JSON data.

To convert a slice of bytes to a string in Go, we need to perform type conversion, as demonstrated above. Running this program will produce the following output:

{"FirstName":"Abraham","LastName":"Freeman","Age":100}

As you can see, we get a valid JSON object that can be used in any way we

want. Note that the email field is left out of the result. This is because

it is not exported from the Person object by virtue of starting with a

lowercase letter.

By default, Go uses the same property names in the struct as field names in the resulting JSON object. However, this can be changed through the use of struct field tags.

type Person struct {

FirstName string `json:"first_name"`

LastName string `json:"last_name"`

Age int `json:"age"`

email string `json:"email"`

}

The struct field tags above specify that the JSON encoder should map the

FirstName property in the struct to a first_name field in the JSON object

and so on. This change in the previous example produces the following output:

{"first_name":"Abraham","last_name":"Freeman","age":100}

Decoding

The json.Unmarshal function is used for decoding a JSON object into a Go

struct. It has the following signature:

func Unmarshal(data []byte, v interface{}) error

It accepts a byte slice of JSON data and a place to store the decoded data. If

the decoding is successful, the error returned will be nil.

Assuming we have the following JSON object,

json := "{"first_name":"John","last_name":"Smith","age":35, "place_of_birth": "London", gender:"male"}"

We can decode it to an instance of the Person struct, as shown below:

func main() {

b := `{"first_name":"John","last_name":"Smith","age":35, "place_of_birth": "London", "gender":"male", "email": "john.smith@hmail.com"}`

var p Person

err := json.Unmarshal([]byte(b), &p)

if err != nil {

fmt.Println(err)

return

}

fmt.Printf("%+v\n", p)

}

And you get the following output:

{FirstName:John LastName:Smith Age:35 email:}

Unmarshal only decodes fields that are found in the destination type. In

this case, place_of_birth and gender are ignored since they do not map to

any struct field in Person. This behavior can be leveraged to pick only

a few specific fields out of a large JSON object. As before, unexported fields

in the destination struct are unaffected even if they have a corresponding

field in the JSON object. That's why email remains an empty string in the

output even though it is present in the JSON object.

Databases

The database/sql package provides a generic interface around SQL (or SQL-like)

databases. It must be used in conjunction with a database driver, such as the

ones listed here. When importing

a database driver, you need to prefix it with an underscore _ to initialize

it.

For example, here's how to use the MySQL

driver package with database/sql:

import (

"database/sql"

_ "github.com/go-sql-driver/mysql"

)

Under the hood, the driver registers itself as being available to the

database/sql package, but it won't be used directly in our code. This helps us

reduce dependency on a specific driver so that it can be easily swapped out

for another with minimal effort.

Opening a database connection

To access a database, you need to create a sql.DB object, as shown below:

func main() {

db, err := sql.Open("mysql", "user:password@tcp(127.0.0.1:3306)/hello")

if err != nil {

log.Fatal(err)

}

}

The sql.Open method prepares the database abstraction for later use. It does

not establish a connection to the database or validate the connection

parameters. If you want to ensure that the database is available and accessible

immediately, use the db.Ping() method:

err = db.Ping()

if err != nil {

log.Fatal(err)

}

Closing a database connection

To close a database connection, you can use db.Close(). Normally, you want to

defer the closing of the database until the function that opened the database

connection ends, usually the main function:

func main() {

db, err := sql.Open("mysql", "user:password@tcp(127.0.0.1:3306)/hello")

if err != nil {

log.Fatal(err)

}

defer db.Close()

}

The sql.DB object is designed to be long-lived, so you should not open and

close it frequently. If you do, you may experience problems, such as poor reuse

and sharing of connections, running out of available network resources, or

sporadic failures. It's best to pass the sql.DB method around or make it

available globally and only close it when the program is done accessing that

datastore.

Fetching data from the database

Querying a table can be done in three steps. First, call db.Query(). Then,

iterate over the rows. Finally, use rows.Scan() to extract each row into

variables. Here's an example:

var (

id int

name string

)

rows, err := db.Query("select id, name from users where id = ?", 1)

if err != nil {

log.Fatal(err)

}

defer rows.Close()

for rows.Next() {

err := rows.Scan(&id, &name)

if err != nil {

log.Fatal(err)

}

log.Println(id, name)

}

err = rows.Err()

if err != nil {

log.Fatal(err)

}

If a query returns a single row, you can use the db.QueryRow method instead of

db.Query and avoid some of the lengthy boilerplate code in the previous code

snippet:

var (

id int

name string

)

err = db.QueryRow("select id, name from users where id = ?", 1).Scan(&id, &name)

if err != nil {

log.Fatal(err)

}

fmt.Println(id, name)

NoSQL databases

Go also has good support for NoSQL databases, such as Redis, MongoDB, Cassandra, and the like, but it does not provide a standard interface for working with them. You'll have to rely entirely on the driver package for the specific database. Some examples are listed below.

- https://github.com/go-redis/redis (Redis driver).

- https://github.com/mongodb/mongo-go-driver (MongoDB driver).

- https://github.com/gocql/gocql (Cassandra driver).

- https://github.com/Shopify/sarama (Apache Kafka driver)

Wrapping up

In this article, we discussed some essential aspects of building web applications with Go. You should now be able to understand why many Go programmers swear by the standard library. It's very comprehensive and provides most of the tools necessary for a production-ready service.

If you require clarification on anything we've covered here, please send me a

message on Twitter. In the next and final

article in this series, we'll discuss the go tool and how to use it to tackle

common tasks in the course of developing with Go.

Thanks for reading, and happy coding!