In most object-oriented languages, exceptions are an extremely powerful mechanism for dealing with unexpected situations that arise when running your code.

PHP, specially versions 7.0+, allows developers to build robust applications by leveraging this feature.

In this article, you'll learn about exceptions, how you can make the most out of their usage, and how to improve your application with the information gathered from occurrences of them once in production.

Ready? Let's dig in.

What is an exception

Technically speaking, an exception is an instance of the Exception class, which implements the Throwable

interface.

The Throwable interface is special because it's not publicly available, which means you can't have your own classes implement it. Well, not directly anyway. If you create a class that extends Exception, then yes, your class is implicitly implementing the Throwable interface.

The other aspect that makes the Throwable interface special is that only instances of classes implementing it can be used in conjunction with throw, which is a special language construct used to break execution. However, unlike die or similar, throw gives you the opportunity to overcome the problem and move on or, at least, fail elegantly.

As in many other languages, exceptions are supposed to be wrapped with try...catch blocks if they are to be handled.

For instance, you have a method that looks somewhat like this:

public function doSomethingVeryUsefulOrThrowException()

{

if ($this->weirdConditionHappened()) {

throw new Exception("Some weird condition happened");

}

$this->doSomethingVeryUseful();

}

If you were to call this method at some other point in your code, you would probably want to use something like the following structure:

try {

$helperObject->doSomethingVeryUsefulOrThrowException();

} catch (Exception $exception) {

$this->handleException($exception);

}

This way, you can clearly separate the happy path from the error-handling logic.

Occasionally, you may need to perform a series of tasks regardless of whether an exception is thrown. For these situations, you have the finally keyword. To complete the example, it would look like this:

public function myMethod() {

try {

$helperObject->doSomethingVeryUsefulOrThrowException();

} catch (Exception $exception) {

$this->handleException($exception);

} finally {

$this->completeProcess();

}

}

This is the case when you need to release some allocated resources. For instance, if before the try you opened a shared file, and the process is supposed to keep on running for a long time, it would be a good idea to close the file as part of the finally clause.

When should an exception be thrown

When you first start working with exceptions, it can be very tempting to throw them every time you find an error. Try to resist this urge. Instead, think of exceptions as errors that can't be anticipated. In other words, if it can be prevented, it shouldn't be an exception.

Let's use an example of a method requiring an email address as a parameter:

public function sendEmailTo(string $recipient)

{

if (filter_var($recipient, FILTER_VALIDATE_EMAIL) === false) {

throw new Exception("$recipient is not a valid email address");

}

$this->doSendEmail($recipient);

}

If you must use this method to send an email message to an address retrieved from the UI, you could rely on the method throwing an exception if the input is incorrect and write your code as follows:

try {

$emailSender->sendEmailTo($_POST['email']);

} catch (Exception $exception) {

echo $exception->getMessage();

}

However, this is not a good way to use exceptions. If you're using the first method, then there's not much you can do to prevent the exception from happening. However, in the second method, you could make the validation before calling the sendEmailTo method.

This is particularly important when the called method comes from code you don't own (e.g., a third-party library). You don't want to depend too much on external factors when developing long-lasting code.

What is the difference between exceptions and errors

In the case of PHP, for a long time (circa PHP5.3), errors and exceptions were quite different animals. However, since version 7.0, they've been brought together under the umbrella of the Throwable interface.

While functions like trigger_error are kept for backwards compatibility concerns, exceptions or Error objects should be preferred.

How to create custom exceptions

One interesting fact about Exceptions is the ability to create your own. It's really easy, too; all you have to do is create a class that extends the Exception class:

class MyException extends Exception {}

Why would you do that? Well, when defining your try...catch blocks, you can have more than one catch for the same try. Therefore, if you make a call to a method that could throw different exceptions given some previously unknown conditions, you might want to react differently depending on which one happens. It would look something like this:

public function myMethod()

{

try {

$this->methodThatThrowsDifferentExceptions();

echo "Everything worked ok!";

} catch (FirstException $exception) {

echo "Things failed for reason one";

} catch (SecondException $exception) {

echo "Things failed for reason two";

} catch (Exception $exception) {

echo "Things failed for a reason different than one or two";

}

}

What can be done when an exception is thrown

There are basically two operations that can be done once an Exception is thrown:

- Handle it.

- Let it propagate.

- Throw it again.

The first is the case when you implement a catch around the call to a potentially problematic method.

Another way to deal with an exception is to do nothing. The code would look like this:

public function myMethod() {

$helperObject->doSomethingVeryUsefulOrThrowException();

$this->completeProcess();

}

If the method doSomethingVeryUsefulOrThrowException does throw an exception, since there's no try...catch around the call, the exception will simply go up to the immediate caller. Therefore, you could use the following:

public function originalMethod() {

try {

$this->myMethod();

} catch (Exception $exception) {

$this->handle($exception);

}

}

The call to $this->handle() would be executed in the context of originalMethod. The same would happen if originalMethod doesn't have its own try...catch; originalMethod's caller would be expected to handle the exception.

However, what if no one handles the exception? Well, in this case, the whole program will be terminated, and the exception message will be shown and saved to a log file or some other default behavior, depending on the PHP configuration.

Finally, there's a third way to deal with a thrown exception. It’s a mix between the first two: handle and propagate. What? How would that be? Let me illustrate with an example:

public function myMethod() {

try {

$helperObject->doSomethingVeryUsefulOrThrowException();

} catch (Exception $exception) {

$this->handleException($exception);

throw $exception;

}

}

In this scenario, myMethod is both taking care of the exception and letting the caller take a shot at it. Would this ever make sense? Let's find out.

Handle or propagate? That is the question

This behavior poses the question of when you should handle exceptions and when you should let them propagate.

The basic answer is, you should handle an exception at the point in the program where something useful can be done to recover from the problem.

The following is an example of something you shouldn't do, although it's unfortunately fairly common:

public function myMethod() {

try {

$helperObject->doSomethingVeryUsefulOrThrowException();

} catch (Exception $exception) {

$this->log($exception);

throw $exception;

}

}

In principle, there doesn't seem to be anything wrong with this, right? Well ... what would happen if myMethod is at the bottom of, let's say, a five-level deep call stack?

Let's make matters a little worse; what if every method in the call chain took the exact same approach (e.g., logging the exception and throwing it back up)?

You'd end up with bloated logs that don't provide much useful information.

You're probably thinking that it never makes sense to re-throw an exception. Let me give you another, perhaps useful, example:

public function myMethod() {

try {

$helperObject->doSomethingVeryUsefulOrThrowException();

} catch (Exception $exception) {

$this->addContext($exception);

throw $exception;

}

}

In this case, before throwing the exception back to the caller, myMethod is providing some extra information that will hopefully be important when troubleshooting.

The answer calls for a case-by-case analysis.

How to leverage Honeybadger for exception handling

Once your application is prepared to throw use exceptions, you'll need to handle them. Hopefully, you'll be able to catch them in time to try some other approach or let the user know that you're experiencing a problem and offer an alternative solution.

However, sometimes, this is not the case, especially when you just finished developing your application, and it's still in beta.

In these situations, you'll want to get as much information as possible about exceptions that happen when users are interacting with your application.

Depending on how your PHP is configured, you'll find this information in a log file. It will look something like this:

PHP Fatal error: Uncaught Exception in script.php:35

Stack trace:

#0 script.php.php(19): MyClass->methodThatThrowsDifferentExceptions()

#1 script.php.php(43): MyClass->myMethod()

#2 {main}

thrown in script.php.php on line 35

Not very friendly, right?

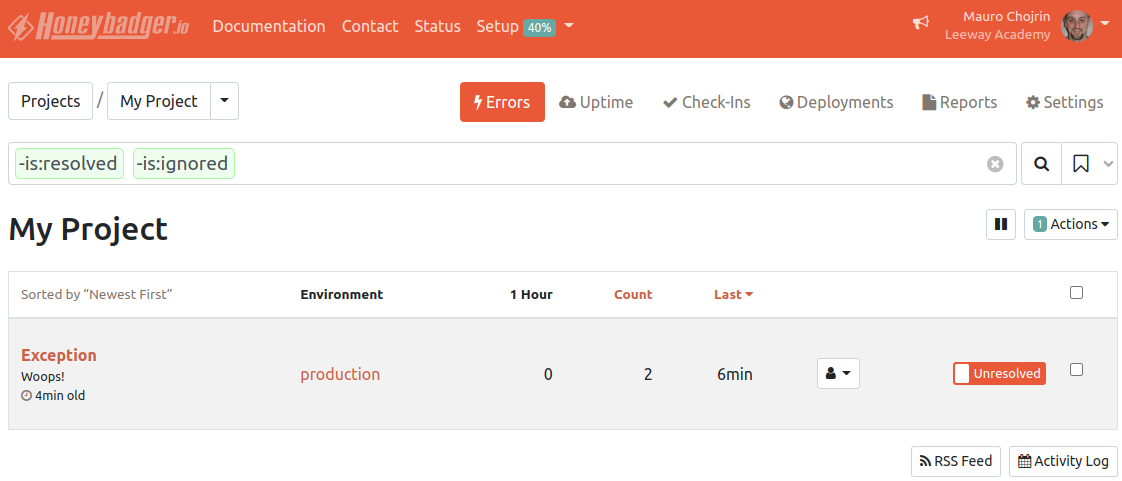

You'd probably be in a much better position if the exceptions were presented to you in a nice UI:

This is what Honeybadger's Dashboards look like.

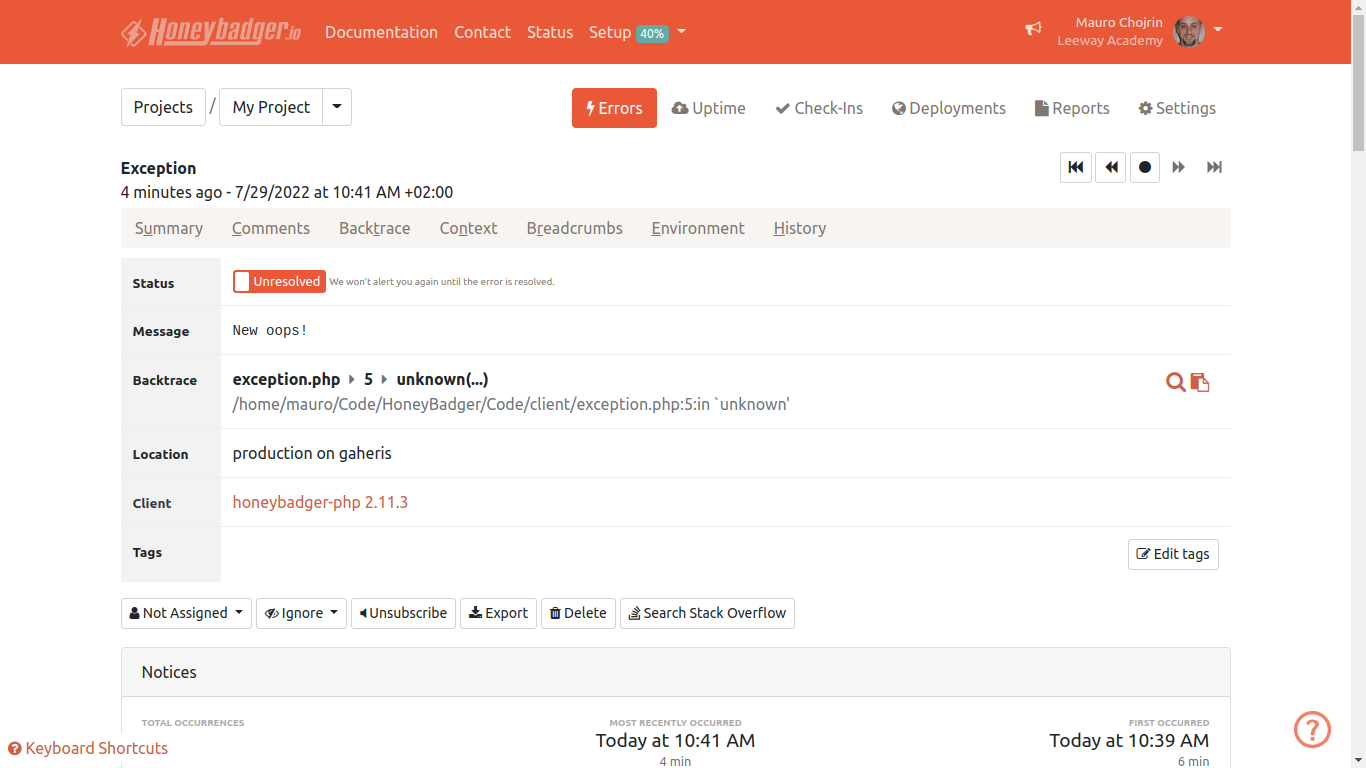

From there, you can go into a much more detailed view, where you can get a lot of contextual information, add comments on the exception, and even assign it to a team member to remedy:

This certainly beats cutting through cumbersome log files looking for a hint, doesn't it?

The best part is that bringing this power to your applications is a breeze. All you need to do is this:

- Sign up for Honeybadger.

- Get your API-Key.

- Add

honeybadger-io/honeybadger-phpto yourcomposer.jsonfile. - Create an instance of the client.

- Sit back and relax.

Here is a code sample:

<?php

require_once 'vendor/autoload.php';

use Honeybadger\Honeybager;

$honeybadger = Honeybadger\Honeybadger::new([

'api_key' => 'MY_API_KEY',

]);;

throw new Exception("Whoops!");

That's it.

You don't have to tell Honeybadger to watch over exceptions. It will do so by default. Therefore, by incorporating Honeybadger into your project, you can rest assured that someone will be notified about exceptions in your code as soon as something bad happens, giving you the chance to proactively fix the issue and delight your clients.